Concept of “Embroidery Workshop”.

This work shop is don by Sae Shimizu and is one of DESIAP’s “Women’s leadership in designing social innovation: mutual learning in the Asia Pacific” program.

Embroidery Workshop

31 May 2022 (Tue) 10:00-12:00

@Sculpture Dept Classroom opposite of the lift near the College Hall

Attendance fees:

Free

Things to bring with you:

pencil (or pen for home craft), scissors (or sewing scissors), an embroidery frame, a needle, and threads (if you have)

As part of the “Women’s leadership in designing social innovation: mutual learning in the Asia Pacific” project, I have organized this embroidery workshop. The curatorial concept is informed by my interest in “intersectionality” which I’m exploring as part of my research towards my MA degree.

“Intersectionality” is an awareness and critical methodology that positions race, class, gender, sexuality, disability, ethnicity, and age in an interrelated manner, in order to explain the complexity of human identity and experience (Collins and Birge 2016) This concept is not only useful for academic enquiries, but also for “empowering” those who suffer from social inequality in the midst of intersecting power relations. This concern is in line with the work of DESIAP.

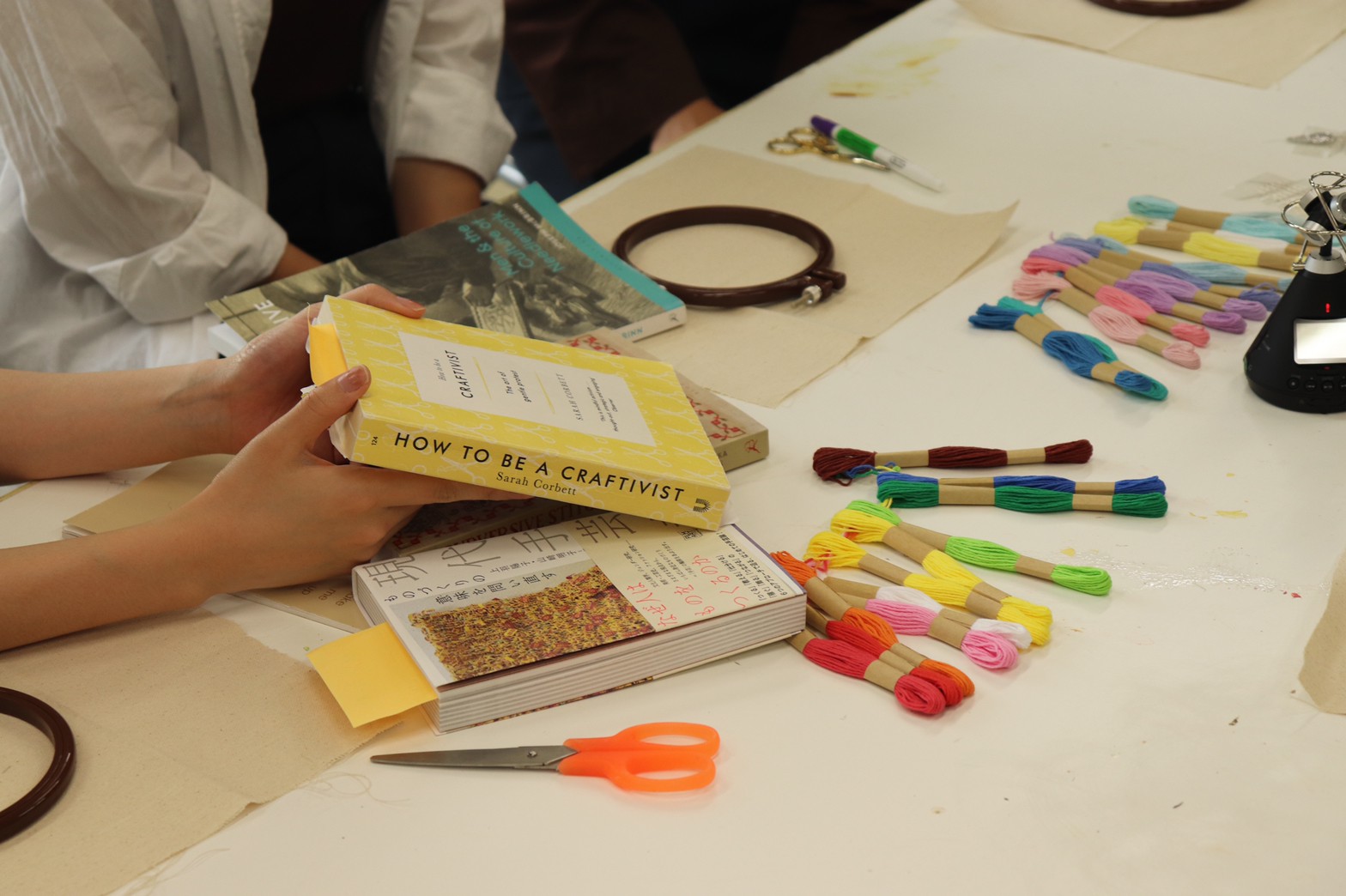

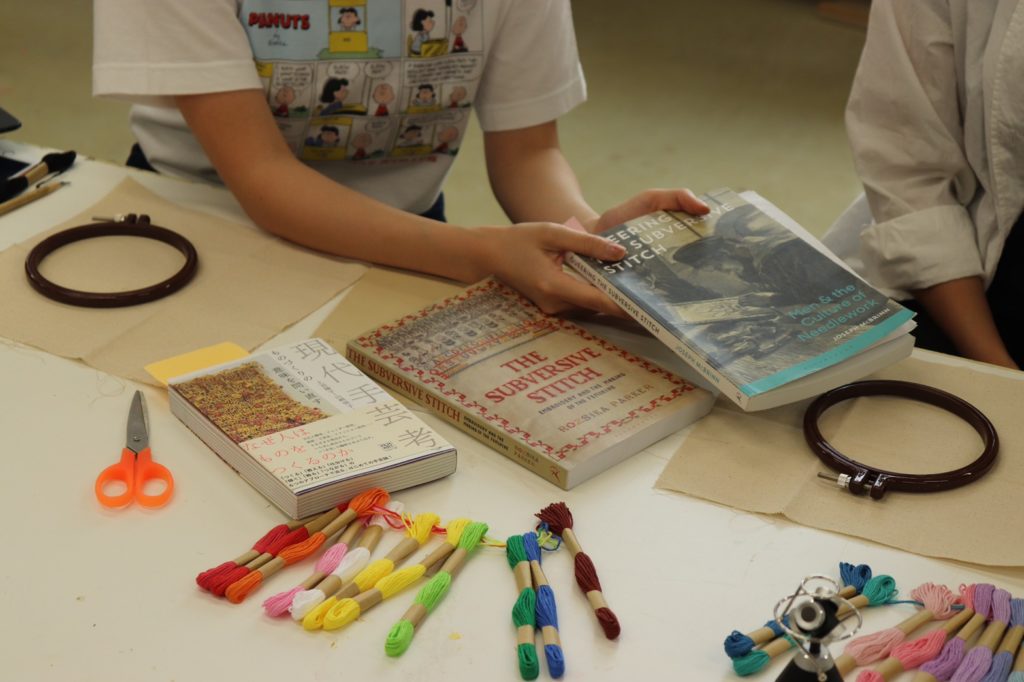

I chose to focus on “handicraft” as an art practice that potentially empowers people. A feminist art historian, Rozsika Parker, argued that historically, embroidery has created “femininity” leading to genderised social inequality in The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (1984). Similarly in Japan, “handicraft” has been marginalized from the areas of “Art” and “Crafts” (Kogei created by professional makers) and has been regarded as a woman’s hobby.

Furthermore, in the field of contemporary art, as the feminist artist Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” (1974-79) demonstrated, by strategically choosing “handicraft” techniques, it is possible to expose the social condition which determines “Women” and minorities. Regarding this phenomenon, art critic Lucy Lippard points out that feminist works such as embroidery and other decorative crafts have attracted attention as “high art”. In recent years, a movement called “Craftivism” that combines “Craft” and “Activism” has emerged. This is a critical activism in which handicrafts forms a platform in a caring environment to address various problems in modern society, for example, inequalities brought by the pandemic of COVID, SDGs concerns including human rights, poverty, welfare, natural environment, energy, etc.

In the first step of this project, I have asked the participants to embroider their “own name” and discuss the story of each name while embroidering with other participants. “Name” is a familiar topic for everyone, and everyone has some stories. This framework makes it, easy for people to with other participants without preparing anything for the workshop in advance. I see “Name” as a symbol of attributes such as nationality, race, gender, class, and religion. Starting with a little talk, the importance is placed on mixing with people of different nationalities and genders, which potentially expands into larger issues that connect one another, leading into meaningful empowerment through embroidery and talking.

How to proceed with the workshop

・ Explanation of the outline of the workshop and participants’ self-introduction

・ Start drafting “name” on the fabric (up to participants which language and shape to choose)

・ Start embroidering (up to participants about embroidery patterns)

・ Start talking (personal stories about names, etc.)

・ Discuss what was found in the topics that came up that could connect with issues such as gender, sexuality, race, and class.

Document the outcomes in the form of a report and/or an exhibition by using texts, audio recording, still photographs, edited transcription of conversations.