【日本語は下部】

Sae Shimizu

(MA student at the Aesthetics and Art History-SCAPe, Kanazawa College of Art)

The local city of Kanazawa, where I was born and raised, is an attractive city for many tourists seeking art and culture, from traditional crafts to contemporary art, but on the other hand, for example, “61.1% of the respondents said they wouldn’t like homosexuals if they were close to them, or rather disliked them, which is the highest in the country”, as shown in this survey, it also has the aspect of being mentally closed. When I was in the second year of undergraduate, I felt suffocated by continuing my studies in Kanazawa, so studied at the National School of Art and Design of Nancy in France during 2017-18. It made me keenly aware of my own hybrid identity as a Japanese woman with ancestorial roots in Korea, and I began to interest in artists of women and all minorities, who were often positioned as “peripheries” in the normative frame of Modern Japanese Art History. After returning to Japan, my supervisor, Yuko Kikuchi, was transferred from the University of the Arts London to Kanazawa College of Art, and I got the opportunity to study issues of “feminism” and “post-colonialism.” And in Yuko’s class, I also was involved in the curation of the exhibition and was interested in the role of a “curator” who can practically return their own research to society. In 2021, I was involved as an internship trainee at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa. And also I curated my first public exhibition “Stories The Mermaids Tell” at the remaining vacant house in Kanazawa. The title of the exhibition was inspired by “The Little Mermaid” drawn by Andersen, who is said to have been a Quier person. The “mermaid” who was deprived of her voice to live as a human being overlapped with the “parties” who are “women”, “sexual minorities”, and have “poverty”. Then, artists with various identities and backgrounds break the forced silence, talk about their narratives, and regain themselves, creating a “place of narrative” that is different from a fixed story. At the same time, it criticizes the structure of discomfort, difficulty living, prejudice, and discrimination that comes from paternalism and heterosexualism.

This introduction has become quite long, but after such activities, Yuko suggested me to participate in the “Women’s leadership in designing social innovation: mutual learning in the Asia Pacific” for my further skill improvement. In this project, I try to deepen the understanding of the theory of “Intersectionality” that I’m dealing with in my master’s research through practical activities. “Intersectionality” means several categories such as race, class, gender, sexuality, disability, ethnicity, and age, which are interrelated and forming, and it’s how to understand and explain the complexity of human experience. (Patricia Hill Collins, Surma Birge) This concept is more than just an academic discipline, it is meant to “empower” those who suffer from social inequality in the midst of intersecting power relationships. Of course, I think the idea of “Intersectionality” is strongly reflected in the DESIAP’s concept.

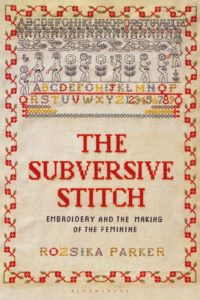

Also, I focus on “handicraft” as an art practice that empowers people. Rozsika Parker who is an art history researcher and feminist said that embroidery historically creates “femininity”, in her “The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine”(1984). Similarly in Japan, “handicraft” has been marginalized from the areas of “Art” and “Crafts (Kogei)” and has been regarded as a woman’s hobby. However, in an era when it was standard for women to become homemakers at the same time as they got married, it is said that the “handicraft” played a role of “care”. I am fascinated by the duality of handicrafts like this. Furthermore, in the field of contemporary art, as the feminist art authority Judy Chicago (1939-)’s The Dinner Party (1974-79) shows, by deliberately choosing a technique called “handicraft”, it is possible to emphasize the socially positioned position of “women”. Regarding this phenomenon, art critic Lucy Lippard points out that feminist works such as decorations and embroidery have attracted attention as “high art”.

As the first step of this project, we will hold a workshop on May 31, 2022. I would like to embroider “own name” with participants and discuss the story of each name. First of all, it will be held on a small scale, but it is important that people of different nationalities and genders gather and connect to each empowerment through embroidery and talking. My mentor in this program Michiko Tsuda, advised me to take a video of the participants’ hands and keep it as a record. Based on this video, I would like to give feedback on the workshop from the perspective of “Intersectionality”.

DESIAP主催「社会的革新をデザインするための女性のリーダーシップ、またアジア太平洋地域における相互理解を促進するためのプロジェクト」への参加にあたって

清水 冴(金沢美術工芸大学大学院 芸術学専攻)

私が生まれ育った「金沢」という地方都市は、伝統工芸から現代アートまで、芸術文化を求める多くの観光客にとっては魅力的な都市ですが、一方で、例えば「身近に同性愛者がいたら嫌だ、どちらかと言えば嫌だという人が61.1%で、全国一位」という調査に現れているように、精神的には閉鎖する側面も持ち合わせています。2017年の学部2年生の時に、金沢で美術研究を続けることに息苦しさを感じ、フランス・ナンシー美術デザイン高等学校で1年間の留学を経験しました。フランスという多文化社会で日本人、女性、在日コリアンのルーツ、といった自身のアイデンティティを強く自覚したことが反映し、日本の美術研究で「周縁」に位置付けられることが多かった「女性」やあらゆるマイノリティのアーティストに関心持ち始めました。帰国後、2019年の学部3年生の時に、私の指導教官である菊池裕子先生がロンドン芸術大学から金沢美術工芸大学に赴任し、私は「フェミニズム」や「ポストコロニアリズム」といった領域を学ぶチャンスを得ました。菊池先生のゼミでは展覧会のキュレーションにも携わり、実践的に自身の研究を社会に還元することができる「キュレーター」という役割に興味を持ちました。2021年には金沢21世紀美術館のインターンシップ研修生として、展覧会「フェミニズムス」および「ぎこちない会話への応答」に関わり、同年10月にはフェミニズムやジェンダーを問題をテーマに、金沢の商店街に残された空き家を会場にグループ展「物語る人魚たち」をキュレーションしました。展覧会タイトルは、クイアな人物だったと言われているアンデルセンが自己を投影して描いた『人魚姫』から着想を得て、人間として生きていくために声を奪われた「人魚」を、「女性」であったり、「セクシャルマイノリティ」であったり、「貧困」を抱えたりする「当事者」と重ねました。そして、さまざまなアイデンティティ、バックグラウンドを持つアーティストが、強いられた沈黙を破り、それぞれのナラティブを語り、自己を取り戻していくことで、固定化された一つの物語とは違う「語りの場」を作り出していくことを試みました。それは同時に、(特に金沢に根深く残る)家父長主義や異性愛主義が、違和感や生きづらさ、偏見や差別の構造を作っていることを批判しています。

前置きが長くなりましたが、このような活動を経て、さらなるスキルアップのためにDESIAP(The Designing Social Innovation in Asia-Pacific)が主導する、「社会的革新をデザインするための女性のリーダーシップ、またアジア太平洋地域における相互理解を促進するためのプロジェクト」(“Women’s leadership in designing social innovation: mutual learning in the Asia Pacific”)への参加を提案していただきました。本プロジェクトでは、アーティストの津田道子さんがメンターとなり、私が自身の修士研究で扱っている「インターセクショナリティ」(交差性)という概念を、実践的な活動を通してより深く理解していくことを試みます。「インターセクショナリティ」とは、「人種、階級、ジェンダー、セクシュアリティ、障害、エスニシティ、年齢などの数々のカテゴリーを、相互に関係し、形成し合っているものとして捉え」、「世界や人々、そして人間経験における複雑さを理解し、説明する方法」です。(『インターナショナリティ』、パトリシア・ヒル・コリンズ、スルマ・ビルゲ)この概念は単なる学問分野以上に、交差する権力関係の渦中で社会的不平等を被る人々を「エンパワーメント」するためのものだと言われています。もちろん、DESIAPのコンセプトにも「インターセクショナリティ」のアイデアは強く反映されているように思います。

また私は修了研究のなかで、人々をエンパワーメントする芸術実践としての「手芸」に焦点を当てています。美術史研究家でフェミニストのロジカ・パーカーは「The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine」で、イギリスの刺繍を取り上げ、刺繍をすることが歴史的に「女性性」を作り出す行為であったことを明らかにしています。日本でも同様に、「手芸」は「美術」「工芸」の領域から周縁化され、女性の手仕事・趣味と見なされてきました。しかし、女性が結婚と同時に家庭主婦になることがスタンダードだった時代、集合住宅の1室に主婦たちが集って「手芸」をすることは、「ケア」的の役割を果たしていたと言われています。私はこのような手芸の二面性に興味を惹かれます。さらに、現代の美術の領域では、フェミニズム・アートの権威であるジュディ・シカゴ(1939-)の《ディナー・パーティー(The Dinner Party)》(1974-79)が示すように、敢えて「手芸」という手法を選択することで「女性」が社会的に位置付けられたポジションを強調することができます。この現象について、美術批評家のルーシー・リパード(1937-)は、装飾、刺繍など、女性的とされたものがフェミニストの作品によって「ハイアート」として注目されるようになったとを指摘しています。

今回のプロジェクトの第一歩として、2022年5月31日にワークショップを開催します。現段階では、5〜6名の参加者と一緒に「自分の名前」を刺繍しながら、それぞれの名前を巡る物語を話し合う、という風に進めていきたいと考えています。まずは大学という小規模での開催となりますが、国籍や性別の異なる人々が集い、「刺繍」と「お喋り」を通して、それぞれのエンパワーメントに繋げることが重要なポイントです。津田さんからは、参加者の手元を写した映像を撮り、記録として残すようアドバイスをもらいました。この映像をもとに、「インターセクショナリティ」の視点から、ワークショップのフィードバックをしていきたいと思います。

引き続き、今後の進捗をこちらに掲載していきますので、どうぞよろしくお願いします。